It was the end of 2012 when I sat down with Patricia Smith. At the time, I was the Interviews Editor for Union Station Magazine, a vital online journal from the first half of this decade. I still think about this conversation all the time. Every answer Patricia gives is deeply generous, incredibly wise, and so rooted in what’s at stake when we as poets choose to tell a story.

There’s not much you can say about her that hasn’t been said, Patricia is a living icon and one of the most important writers of our, or any, American generation. You know the really brave poem in any good collection, where the degree of difficulty is 11? there are 999 ways to say it wrong? and only one to get it right? and only if the poet is at the height of their craft and can somehow not look away from the most flammable of subject matter? Patricia’s books are that poem, one after another, start to finish, fully realized. Unflinching is probably the most overused blurb word in the whole blurb lexicon, and it’s more often than not, if we’re honest, hyperbole—but Patricia is actually UNFLINCHING. Each of those blurbs scattered across poetry collections throughout the country are in essence referring to her.

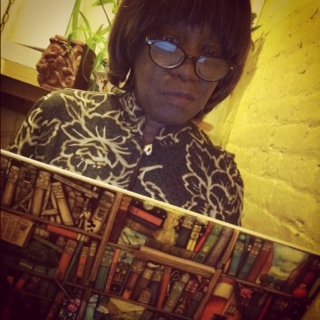

This was right after Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah came out. Patricia had, that summer, done a reading in my old living room for about 50 writers from the greater New York City poetry world. The room was dark and midsummer-hot. Patricia sat in a fold out chair between the vortex of two rattling fans. She read for over two hours, and then answered questions for another 45 minutes while we all tried to, I think in some ways, parse out the meaning of life, or why this thing we’d given so much energy to, writing, oratory, processing, was worthy of a life’s work. We huddled together on that sizzling June night, as she read poems and answered each ravenous question. We stewed in our own sweat, wonder, and renewed fortitude.

It was in the spirit of that night that I asked Patricia to meet me at Grounded in the West Village, where we took out our laptops, opened up gchat, and Patricia let me ask her questions for another two and a half hours. The answers are as relevant now as they were then, and I’m excited to bring this interview back onto the internet. I hope it’s as meaningful for you as it continues to be for me.

——–

Jon Sands: Your poems often freeze a moment, and find something locked in time, teeming with life. They recognize, also, the moments or people gone from these snapshots. (In “Still Life With a Toothpick,” we see the car accident that claimed the lives of your father’s parents.) In what ways do you feel poetry and photography relate?

Patricia Smith: I look at life as a continuous scanning of narrative, and I consider a poem the moment when that narrative is stunned, when it can’t move forward without further comment. I’m hooked on the visual, hooked on transporting the readers into the moment and rooting them there. But while they’re there, they remember what came before and they’re straining toward what comes after. So the “borders” of the snapshot blur, the moments bleed one into the other. In the case of “Still Life With Toothpick,” it took me a long, long time to snap that photo. It hurt. But once it was there, clear and uncompromised, I was able to move on with my story.

JS: These snapshots around family sing in a way that is hard wrought. How much does research play a part? Either emotionally, or dates, times, and characters. What’s your relationship to family secrets?

PS: In a way, my whole family is a secret. When my mother moved from Alabama to Chicago, she vowed to leave all “that down-South stuff” behind, to begin anew. She was ashamed of being from such a backwards place, and the glittering promise of the city had thoroughly seduced her. So when I questioned her about anything before the time her Greyhound pulled into Chi, she would give me the pity-eye and say “That ain’t got nothin’ to do with you.” So an entire segment of my life was shut off, just like that. Whenever my mother found out that I was questioning other relatives, she’d chastise me. She has a suitcase full of curled-corner Polaroids of people she refuses to identify. So when she is gone, so is my history. My father, the storyteller, died before I could question him.

So now I’m a digger. “Jimi Savannah” was my first attempt at digging, imagining what I couldn’t possibly know and investigating what I could.

JS: And do you know something—emotionally—after writing Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah, in regards to your childhood, or your perception of your parents, that you didn’t know before?

PS: I know that NOT knowing doesn’t make me less of a person, or less of their daughter. I understand my mother’s mindset, although I still resent it. However, I may have further canonized my father, the parent I’m most like, because I feel that he’s the storyteller that burns in me, and I’m almost giddily grateful for that. I can see my parents’ lives before Chicago, I feel what they hoped for, I realize how disappointed they were when they arrived. I still can’t talk to my mother about it—but I’ve found ways to let her know that I’ve opened in many ways, and that there is a place for her, as she is.

JS: This idea of, we’ll call it “disappointed upon arrival,” is a foundation of this narrative. There is a general migration in the book centralized around hope, often accompanied by devastating backlash. In poems like “One Way to Run From It” (“Chicago, frigid siren, murmurs Come // while hiding how she fails”), we see the migration of southern African-Americans toward the idea of freedom. This is coupled with Motown selling love that the real world can’t possibly live up to. (“Less than perfect love was not allowed / and every song they sang told me to wait.”) What role do you feel hope has played in the history and landscape of oppression in America?

PS: Hope is the dangled bait. Hope etched a vision for my parents that was impossible to achieve. Anyone who paused long enough to pull the promises apart would see them for what they were. The factories in the north needed people, and my parents were people. They were people who were less than people in the place where they lived. All they wanted was to be considered, not to have to step off the sidewalk into the street when a white person walked toward them. There are jobs. There is housing. There are white people who respect you. Your children will be real Americans. Their schools will teach them what they need to know to live and work among us. It hurts me to think of how hard they held onto those promises. So they took that huge risk, and were funneled into a portion of the city that was nothing like what they’d hoped—roach-riddled tenements, menial jobs, failing schools, concrete, concrete, concrete. Downtown Chicago was a glittering beacon, a place close but millions of miles away, where department store cashiers spat on the path you walked. (I feel like I’m getting away from the question, but I can see my mother, growing smaller whenever a white person is in sight, trying to teach me how to speak and walk to gain their favor). Imagine how confounded my parents must have been—and now, a child to raise, and no idea of how to teach that child the physical and psychological boundaries of city. I was left to my own devices while they tried to reconcile their disappointment and—hallelujah, there was Motown. I looked to the songs for guidance, for a roadmap to the world that had eluded my parents, but which surely waited for me. What role has hope played? It is the dangled, unreachable bait. “Your key to acceptance——which you really crave—is your belief in our belief in you.”

JS: “Hallelujah, there was Motown.” The music plays all kinds of rolls in this book. But, in regards to Motown’s sale of a life that didn’t exist (“There once was a song that took hold/ of a child, cause the story it told/ made her feel flushed and held/ until she was compelled/ to give in to the lies that it sold.”), what responsibility do artists have to own up to the images they sell? If any? Does this expand to other genres or mediums?

PS: It’s crazy to think that any singer, musician, poet has a responsibility to be rooted in reality. The point of being an artist is to skewer what’s before us, to present alternatives. That’s why we seek out music when we want out of the bodies we’re living in. It takes us elsewhere. We know how relentlessly art can lie to us, and we ask for more, because reality’s a drain. I was skinny and knock-kneed and pimpled and my hair was an overpressed disaster and because I was good in school I was ostracized, and I would have died without Smokey’s croon, telling me that an inevitable blooming was just right around the corner. Dangled bait. I don’t think I would have survived without it. Just think of how many Motown songs BEG for a woman’s attention, a woman’s return—the singers were literally on their knees. That was the kind of deception I needed just when I needed it. Artists have no responsibility except to see what we see and then make us see something else. There always has to be SOMETHING ELSE, and if possible it should be SOMEWHERE ELSE. And yes, there’s quite a bit of that going on in poetry—poets in Westchester imagining the thug life, poets in Camden crafting daisies and musing on sunsets. Jesus, yes. Get me out of here.

JS: This reconstruction of reality, it feels like you do it, often by traveling backward first. Teahouse of the Almighty, Blood Dazzler, and Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah all explore the people we have lost. I’m thinking specifically of “In the Audience Tonight” from TOTA, where the ghosts of two fathers come to watch their children on stage. We see homage to past performers (i.e. Mary Wells), writers (i.e. Gwendolyn Brooks), and without a doubt to your father. Do you feel, at any point, like those that have passed on are watching you? Or like they have a stake in how you tell the story?

PS: Years ago, I was performing in an arena in Osaka, Japan, an arena filled with approximately 25,000 Japanese businessmen. (Long story.) While I stood there, I saw the face of my father and I thought to myself, “Daddy, look at this. Look at all these people. Look how their faces are turned up, how they’re waiting for me to say something. Waiting. For me.” From that moment on, I knew he was with me, that he had worked with me toward that moment. When I first told my mother that I wanted to be a writer and she said, “Only white men do that,” I had no choice but my father. I’m an only child. When I’m up in the middle of the night writing, if I woke my husband with a loud laugh and what sounds like a running conversation, he’d know that my father and I were amused by a line, or that I was sharing a story about some way I’d been pulled or pushed that day. He’s necessary to the process. I even filter my friends through my father’s eyes, which has, believe me, gotten rid of quite a bit of quaff (don’t know if I’m using that word correctly, but it feels good). I knew Gwen, I loved Mary Wells, but in a way it was my father who introduced me to them both: “Good gals. You should get to know them.”

JS: That is incredible…Religion is a buzzword throughout this collection, be it in “Guess Who’s Closest to Heaven,” or in each specific character. Your mother’s religion is in the church and Jesus. Your father’s religion is Patricia (“conjuring his own religion and naming it me.”), and Patricia’s religion is Chicago. (i.e. The World. “I weep on cue. I finally found religion, named it you.”) When you think of this definition of religion, or the thing that defines you, that sends you out to conjure spirits, what would you say is your religion now?

PS: Once I was in a middle school in Chicago, supposedly doing poetry. The kids weren’t havin’ it. I was an interruption in their day, welcome (because they didn’t have to do any work) but resented (who did I think I was?). I spent the whole time waxing poetic to the disinterested throngs, working hard to pull them in with ANYTHING, but they’d already made up their minds. Blanket rejection. Glaring. Gumpopping. Tooth sucking. Muttered invectives. In other words, POET FAIL. I dragged through my time there, already wondering what I’d done wrong and what I could do to be better. The last bell rang, I headed for my car. Just as I put my key in the lock, one of my most vehement antagonists (“You ain’t my mama. You can’t make me listen to nuthin’”) came up and pressed something into my hand. I was startled at first, and I’m ashamed to admit that I thought he was going to mug me. Instead, I looked at the sweated, folded up little piece of paper he’d urged into my hand. I knew without looking that it was a poem, a spectacular risk for him, something he couldn’t admit to in the presence of his peers. That hot little connection, palm to palm, reeking of desperation and beginning? Religion.

JS: I’ve heard you speak about that release when someone reads/hears a story they themselves have been keeping silent. The power there. There’s a poem in Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah called “All-Purpose Product.” It shows the author’s mother applying Lysol to the back of her neck in an attempt to lighten her skin. It raises countless questions, but in truth, it also answers most of them. (How did it affect the speaker’s relationship to her mother? Can this be true? Did she survive?) One question I would like to ask is how this affects your relationship to those that recognize and then vocalize moments like this from their own past?

PS: First of all, the story is true. My mother was never, never satisfied with the way I looked, which didn’t meld with her idea of what it took to be “successful” in the north. She could insist that I speak white, but she was frustrated by all the things she couldn’t change. We’d be watching television, and she would just reach out, wordlessly, and squeeze my nostrils together. Hold them there for the length of an entire program. My childhood was filled with my mother’s attempts to correct me. And yes, I survived, but not without recurring wounds. I do that poem and inevitably someone—usually a black person, but not always—approaches me with a story. Tide in the bathwater. Bottles of rubbing alcohol and sponges. Artra Skintone Cream (meant to “even out” dark spots) slathered on relentlessly and left to “work its way in” during the night. It’s the voicing of trauma. And since the secrets prevalent during my upbringing were part of many other upbringings, the poems become a way to bring even a bit of voice to the surface. Shared pain is somehow easier. My relationship to my mother? Ummm. Like I said before, I’ve learned to know who she is, and what happened to make her that way. Sounds strange, but she really just wanted the best for me. Unfortunately, being the best meant being as white as possible. There was a whole generation of colored folks, first generation up north, who had to contend with the sudden, almost violent, shifting of their parents’ perspectives. They were presented with options they didn’t have before, and one of those options was raising a NORTHERN child, whatever that meant.

JS: As a child of that generation (in particular as someone who is in the business of remembering), how does that affect your relationship to mothering or grandmothering?

PS: I guess I’m more upfront (with both child and grandchild) about the pitfalls of unbridled hope. I talk a lot about ugly, which makes pretty all the more memorable. Lately I find myself exploring my old neighborhood with Mikaila, telling her things about her father’s past that I’d hidden, and I tell my son that my love for him is wide open, despite the fact that my dreams for him were pretty much summarily dashed. I guess that’s the realization that means the most to me. That my children, both of them, are worth everything to me, and I need to make them see that that never wavers, even in the face of those who consider them worthless. That’s kind of a reverse lesson from my mother.

JS: There’s a section in SBJS, “Learning to Subtract,” that couples learning about death from the nightly news (i.e. Death tolls in the Vietnam War, Richard Speck’s murder spree of eight nurses on the South Side of Chicago) with the curiosities of learning about gender and sexuality (i.e. “She (Karen) smelled like what I couldn’t stop swallowing.” “i do not know the name of my immediate/ future, wouldn’t recognize the hot snap/ of the word cock, i don’t have a clue/ to that thing’s unerring purpose, but ouch,/ a vessel deep in me is already calling.”) In what ways are these discoveries related?

PS: All rooted in secrets. My mother would plop me down in front of the television (one of the huge floor models) with no explanation of anything I might see. So the war (unedited) spilled into the living room. I was mesmerized by it, half hoping it was a movie, knowing it wasn’t. Where was it? Could it hurt me? Is that where my daddy is? How far away is Vietnam? And the relentless scroll of numbers, which I finally realized meant lives. Then there was sex, also a secret—so much so that when my period began at 12, I hid my underwear in a record cabinet because I thought I was dying and didn’t want to upset my mother with the news. One day, nothing. Next day, bleeding from the crotch. Terminal illness, right? Funny, but I didn’t identify the thing with Karen as sex. It was just an overwhelming discovery I thought came with age (!), but funny how I knew instinctively that it was something I wasn’t supposed to talk about. I wanted a secret of my own, and that was a doozy. Neither one of those experiences (discovery of war/death, discovery of sex) would have happened the way it did if I had a mother I could approach, who didn’t always find fault with the me I was. I just knew that I’d be punished for being scared (war) and for feeling good (ah, Karen).

JS: In reading “Building Nicole’s Mama” from Teahouse of the Almighty, we see the direct influence of the author’s documentation of loss and homage, enabling the student, Nicole, to dream of writing about the loss of her own mother. Was there anyone (in their work or their person) that contributed to what it took to build this monument of a book to your parents?

PS: Two people. My husband, and Afaa Weaver. My husband has one of the sprawling, maddening families, which he can trace back to the 1600s, and I have my mother and a suitcase full of unidentified Polaroids. I loved him talking lineage and ritual—and although I’d convinced myself that I had no discernible history, he nudged me toward one. “Find what your mother won’t say,” he told me. “You know her now. Imagine her then. And your father, you know.” I think that feeling surrounded and included in HIS family gave me the strength to look for my own. And yes, there was pain there, but it’s pain linked with revelation. To know where you are rooted in the world, you need to know your parents. And I think I know enough of mine now.

And Afaa—he is the first poet I know who reveled in family, and his story was fractured and not-at-all neat around the edges. He celebrated loss in a way I couldn’t believe. He laid so much of himself bare and I envied him that access. In particular, he talked about his father and I saw my father in his. Listening him and reading him helped me get rid of my lingering remnants of shame about my past.

JS: There is so much of your father here. Has that in any way been a seed that is related to your current project, When Black Men Drown Their Daughters? How did this rise for you as a story that needed telling?

PS: I guess it was a seed. I’m so insanely close to my father (I’m tempting to say “my father’s memory,” but that’s not right), that the idea of a man tossing his infant daughter over a bridge just didn’t compute. I needed to see if there was any possible way to explain that. And I wanted to contrast it with what I imagined my father’s love for me to be. The project is a mess right now, all over the place, not nearly as neatly defined as I’d like it to be. But I think that’s necessary. And how did it come to me? A news story I couldn’t shake, and then another news story just like the first one. Two men. Two babies. Two bridges. Both in Jersey (!). You know how something clings to you, no matter how hard you try to rid yourself of the responsibility of the story? That’s what happened. I knew I’d be opening up a huge can of emotional worms, that I’d probably be accused of wagging a finger at black men (who, I’d be reminded, have enough problems), but that doesn’t change the fact that two black men drowned their babies. I guess I’m just exploring, and I’m already scared by what’s rising to the surface. But the surface is where the writing’s waiting.

JS: I’d like to shift here, at the end, to a question that I would love to believe I will ask differently than you have had to answer, I’m sure, over and over, through the years. But maybe I’ll just be one more cherry on the poetry slam crossover cake:

You haven’t participated in a poetry slam since 1995, yet I see you billed, at times, in festivals or readings, as a “performance” poet or a “slam” poet. I’m usually like, “Patricia was a National Book Award finalist! Why would she be billed as a performer?” There is also the FACT that you give an incredible reading. In regard to your current participation in the cannon, what are some of the challenges and/or triumphs that have come with participation in communities that value the creative medium of reading poetry out loud?

PS: I’m constantly trying to explain to people that the slam is just something some poets chose to do with their work—temporarily. It’s a means to discovering your work, your voice, your root. It’s a crapshoot, a recreational activity, the trendy/sexy thing that gets people into the seats. I wouldn’t want to come up any other way, right at the beginning of it, in the midst of all that heat and chaos. But if I had known how much of an albatross it would become, how hard it would be to turn it off and move on, I might feel differently. I have to fight for an unusual position—I sit at the juncture of craft and performance, an artificial construct to be sure, but there nevertheless. As soon as we speak/write out loud, we’re urged to represent, to identify our tribe and to swear our allegiance to it.

The so-called academics didn’t want to have to explain my presence in their midst, so I become the allowed exception. Granted, I know that many people are dazzled by the slam (and performance poetry, which are mistakenly interchanged with alarming frequency), but the idea that good performance neglects craft and that craft cannot be performed well is ludicrous. I guess that when I moved on from the slam, I should have automatically started mumbling into the mic. But I learned SO much coming up the way I did, and I will always care about how my poem reaches the audience. I’m gradually realizing that the problem of my categorization is not MY problem. I’m ostracized and resented because I’ve done the work. I’ve identified the best real estate on both sides of the fence and I’ve lived there. I can’t be responsible for the performance poets who are still crossing the country on Greyhound, sleeping on friends’ futons and performing for pass-the-hat. I can’t be responsible for the Pulitzer winner who has to be reintroduced to the idea of a microphone at every reading. I will continue to correct those who insist on identifying me one way and one way only—and I will continue to revel in the fact that, at least for me, poetry is a living pulsing thing that deserves every ounce of my attention. It deserves to be written well, and those written words should move out into the world with fierceness and resolve.

JS: What a gift. What giving. Patricia, thank you so much for joining us here at Union Station. Forever and ever. What a gift.

PS: I must admit…this was gorgeously ODD. But I am in the presence of someone I love and admire, which is always good. It’s nice when gifts go both ways.

Patricia Smith is the author of eight books of poetry, including Incendiary Art, winner of the 2018 Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award, the 2017 Los Angeles Times Book Prize and the 2018 NAACP Image Award, and finalist for the 2018 Pulitzer Prize; Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah, winner of the Lenore Marshall Prize from the Academy of American Poets; Blood Dazzler, a National Book Award finalist; and Gotta Go, Gotta Flow, a collaboration with award-winning Chicago photographer Michael Abramson. Her other books include the poetry volumes Teahouse of the Almighty, Close to Death, Big Towns Big Talk, Life According to Motown; the children’s book Janna and the Kings and the history Africans in America, a companion book to the award-winning PBS series. Her work has appeared in Poetry, The Paris Review, The Baffler, The Washington Post, The New York Times, Tin House and in Best American Poetry, Best American Essays and Best American Mystery Stories. She co-edited The Golden Shovel Anthology—New Poems Honoring Gwendolyn Brooks and edited the crime fiction anthology Staten Island Noir.

Jon Sands is a winner of the 2018 National Poetry Series, selected for his second book, It’s Not Magic (Beacon Press, 2019). He is the author of The New Clean, the co-host of The Poetry Gods Podcast, and a curator for SupaDupaFresh, a monthly reading series at Ode to Babel in Brooklyn. His work has been featured in the New York Times, as well as anthologized in The Best American Poetry. He teaches at Brooklyn College, Urban Word NYC, and facilitates a weekly writing workshop for adults at Baily House, an HIV/AIDS service center in East Harlem. He tours extensively as a poet, but lives in Brooklyn.

——————————